It’s only natural that a small nation of some 11 million people with a cultural heritage dating back some 3,500 years and a – turbulent to say the least – modern history can speak of a musical legacy so diverse.

Much like the passions of a people, so too, music is a truthful reflection of a particular culture with its ups and downs, its unique traits and its stereotypical (mis)demeanors.

Geographically located at a crossroads of civilizations, with one foot in the more circumspect West and the other in the mystical East, in the midst of the tempestuous Balkans, Greece has for centuries been at the heart of where it’s all happening.

“Pick a random stone anywhere in the world and you’ll discover a Greek underneath,” the saying goes, and no doubt about it you’ll find Greeks making history throughout antiquity and during Byzantium, and much later building their homes (and communities) everywhere from Egypt, Turkey, Northern Italy and Russia to Argentina, Germany, Australia, Canada and the US.

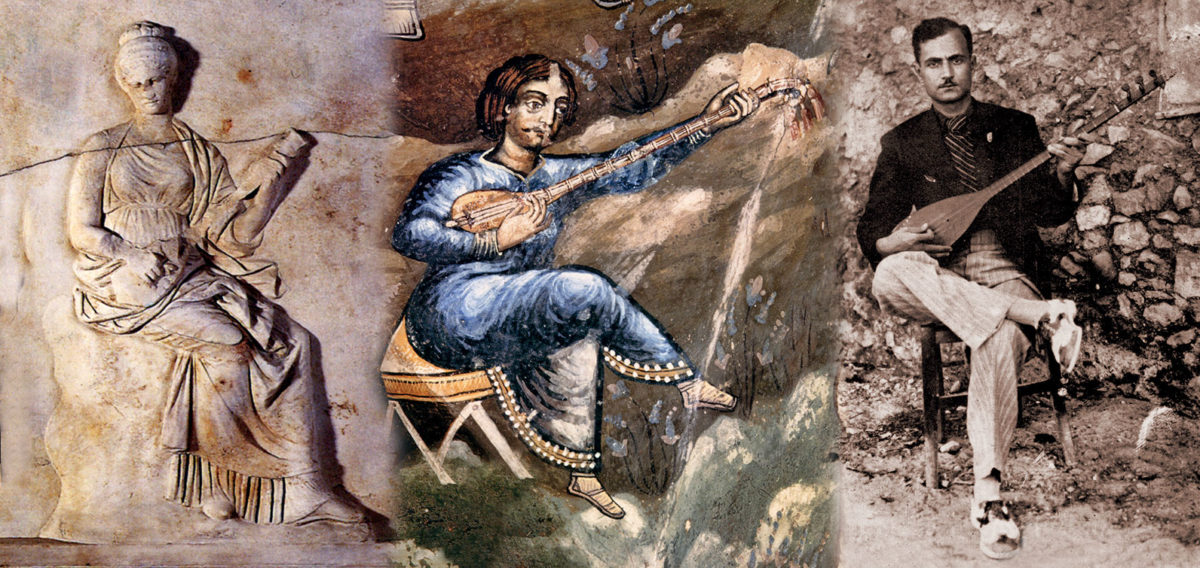

Greek Music Through Time

Every single moment in this long 3,500-year history is somehow infused in the Greek psyche and thus conveyed through its music – a music with a continuance in time. This explains the sheer variety of distinct genres, styles and idioms, and the difficulty in making it… short.

“Greek Music 101” is not about Greece’s long history and its role in and influence on the emergence of each musical genre. Jamming 3,500 years of Greek music into a single blog post titled “Greek Music 101” would be foolish to say the least. I can’t even begin to introduce the genres and idioms that have entertained this small nation throughout the centuries.

But let’s face it: the dances we see depicted on ancient vases dating to Minoan times (2600-1100BC), are still danced in Crete today. The stringed “varvitos” held fondly by Lesvos-born poet Sappho (aka the 10th Muse) in 628BC-568BC, is basically a plucked version of the modern-day lyre, ever present in Greek island music.

Goat-footed Pan, god of the pastures, played his magic pipes to enchant forest friends and foes alike. A similar-styled flute still lulls us today in the same mountains of mainland Greece.

A large part of these ancient sounds and instruments grew to become the mystical music of Byzantium, which in turn shaped the sounds and scales of the demotika – folk songs that are still danced and sung to this day. Songs and dances of courtship, marriage, rebellion, musical mocking tales such as Crete’s rhyming mantinades and dark dirges wishing off the dead, date as far back as the early 17th century.

And throughout this time, musicians continue to hand down their secrets from generation to generation. The Halkias family, for instance, continue their long musical tradition for over 150 years. Here Petro-Loukas Halkias interprets traditional Epirot song “Skaros” with his by now trademark clarinet:

Greece’s long and winding road, as well as its delicate geographical location, have played a decisive role in the emergence of fresh musical styles, such as the embellished music of the Asia Minor Greeks, known as the Smyrneiko or Politiko depending on whether it was played in Smyrna or Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul). Here the legendary Roza Eskenazy performs traditional “Dimitroula Mou” (My Darling Dimitroula):

Also known as the “Cafe Aman”, this musical idiom was an animated mélange of Eastern percussion-based rhythms and vocal acrobatics creatively tied in to the traditional sounds the Greeks had taken with them from their native lands. Thus the heavy-footed zeibeikiko (named after Anatolia’s outlawed Zeybeks) and the erotic tsifteteli (belly dance) mingled with the traditional kalamatiano and hasapiko, giving birth to a new music: the song of Asia Minor. Here an audio taste of a sensual tsifteteli with Eskenazy:

Song of the Underground

In the meantime, underground, behind closed doors, in the hash dens, prisons and ports of Piraeus, Patras and Salonika, one could overhear the weeping bouzouki, the twang of the baglamadaki and the steel-string guitar that had come to take the place of the laouto, oud and fiddle, which held together the traditional demotika. The song of the downtrodden is born: the rebetiko or the “Greek Blues.”

►Where to get the genuine rebetiko experience

In 1922, the Asia Minor Catastrophe saw the sudden influx of thousands of expatriated Greeks to the port Piraeus and into the Greek capital. As a result, Greek music experienced the parallel development of both the Asia Minor song and the rebetiko. The days of wealth and prosperity were over. The Greeks of Asia Minor were faced with a new harsh reality ahead of them. Greece in the 20s and 30s was ravaged by war. There were no jobs and people were dying of hunger. Stella Haskil performs “Kaigomai Kaigomai” (I’m Burning Up):

As if to “lighten up” the country’s predicament, Elafry song surfaced primarily to back up theatre and revue performances with musicians playing live on and behind the scenes. With a subject matter focusing on love and enjoyment, the elafra (aka “European”), were influenced by French chanson, Italian Bel canto as well as operetta. These mainstream works, “musical artefacts” of sorts, also marked the history of Greek music, reflecting the social reality of the era. Here Danae (Stratigopoulou) sings an Attik song: “Einai I Agapi Himera” (Love is an Illusion).

During this time and despite its ban, the rebetiko flourished into a fully-fledged genre and something even greater: it had become a way of life with its own dress and moral codes. The rebetes (translating into “rebel”) lived on the fringes of society, did things their way and sang about them. The rebetiko also expressed the anxieties of the working classes, paving the way in the late ’60s for the laiko, featuring a larger band and focusing more on the vocals with lyrics mostly about love lost and social inequality. The immense Stelios Kazantzidis interprets “O Ergatis” (The Worker).

Entechno: The Art Song of Greece

At the same time, in the upper echelons a new sound is brewing. Entechno, or art song, came to the fore concentrating on the lyrics and dressed in a more refined sound. Steering away from the traditional sound but retaining the traditional rhythms, entechno is a fully orchestrated genre with or without the bouzouki placing more weight on the canto. Internationally acclaimed Nana Mouskouri takes her fledgling steps besides Manos Hadjidakis in “Ela Pare Mou ti Lypi” (Come Take My Sorrow Away).

Due to civil unrest at the time and the forced establishment of the 1967 dictatorship, political song was born of art song. For the first time in Greek music history, the verse of Greece’s greatest poets would become the word of the masses thanks to inspired composers like Mikis Theodorakis, Manos Hadjidakis, Yannis Markopoulos and Christos Leontis to name but a few. Grigoris Bithikotsis sings the lyrics of poet Yiannis Ritsos to the music of Mikis Theodorakis.

►Greek Political Song: Get up, Stand up, Sing Out for Your Rights

At the same time, in the mid-60s early ’70s, restless young musicians formed bands, moving away from the traditional Greek sound. We see the emergence of the first garage bands paving the way for local attempts at pop and rock music. Though most of these groups were short-lived, they served as springboards for the careers of some of the country’s finest artists including Demis Roussos, who started off playing bass in Zoe & The Storms, became lead singer with Aphrodite’s Child only later to take the world by storm. The now universal Vangelis (Papathanasiou) was also a founding member of Aphrodite’s Child and The Forminx. And there was a plethora of foreign-named groups such as The Idols, The Charms, Socrates Drank the Conium, The Daltons, The Forminx who tried their hand at progressive pop and rock. One such group, The Daltons perform “Jesahel”.

At about roughly the same time you have the angst-filled alternative rock groups like Mousikes Taxiarchies and cult personas like Pavlos Sidiropoulos, and Nikolas Asimos bringing to the fore an urban sound (through underground cassette tapes), which articulates Greece’s newly emerging inner-city reality: drugs, sex and rock ’n’ roll.

The blaring ’80s was a period of drastic socio-economic change for Greece, which is also manifested in local music and art. This is a time of inconspicuous consumption in all its glory… The very Greek laiko of the ’60s takes a more popular turn with traces of pop music (and performance) sneaking in and taking radio stations by storm. A new sub-style is born, first looked down upon as being of lesser quality but later expressing a newly emerging Greek society. With a more electric feel – drums, electric guitars, synths – pop-laika retains the bouzouki in the lead, with less focus on vocal talent and social issues, and more attention to lyrics about love lost (or found) and the pains of amour. This style is among the most popular in Greece at the moment and the one you’re bound to listen to in one of those massively huge nightclubs where showering performers with whole baskets of flowers is a must.

Greek Hip-hop

The early ’90s, saw the advent of yet again a new style. This may not be New York, but city youths – skaters, graffiti artists and DJs – from the western suburbs of Athens and the lesser off neighborhoods of Piraeus take a stab at hip-hop and do some of their own rappin’. What starts off as a handful of restless souls venting their anger to a beat-filled sample, turns out to be one of the highest-selling genres on the local market, breaking through to the mainstream in the mid-90s and fanning into several sub-styles in the last decade. Active Member, Goin’ Through and Terror-X-Crew (aka T.X.C.) were among the first to give it a go.

So if you’ve read this far, I think you can only agree that despite its size, Greece boasts one of the wealthiest musical legacies in the world. And for a newcomer, even beginning to understand it can prove to be a challenge.

I hope “Greek Music 101” has managed to draw you into the wonderful world of Greek music, a music that continues its journey through time, making stops in history and carrying with it a sound for the next stop… adding to the whole, which we call the “Greek soul”.

In the words of Greek poet Kostis Palamas (1859-1943):

“Songs of Yiannena, Smyrna, Constantinople,

Kostis Palamas

Lingering songs of the East,

Songs of sorrow,

Oh how my soul is drawn to you!

It flows to your music

And travels on your wings…”

🎶 For more about the diversity of Greek music and to get a taste of what travelers should experience when they visit Greece, check out The Greek Vibe via podcast as I speak to Honor Morrison and Low Season Traveller®